James Beveridge Documentary Pioneer

The National Film Board of Canada

Grierson had a plan for Dad. He wanted to hire him to work at the future NFB. Grierson immediately sent Dad to London’s GPO (General Post Office) Film Unit to learn about the craft of documentary filmmaking. Two months later, World War II broke out. Dad was dispatched by Grierson to Ottawa to establish the NFB and launch a propaganda unit in support of the war effort. It was 1939.

One of Griersons’s greatest contributions to Canada’s documentary scene, was the drafting of the Canada Film Act, which established the NFB as a permanent Canadian entity. The NFB had a mandate to “interpret Canada to Canadians and to the world”. During WWII the NFB had two separate but related strands of production. The first, “World In Action” and “Canada Carries On”, were the mainstream newsreel propaganda series that were distributed to the USA and throughout the Commonwealth, promoting the war effort and putting Canada on the map. But Grierson also promoted another strand of uniquely Canadian films — films that explored the many aspects of Canadian culture and geography. Distributed domestically through church groups and community halls, these films helped to define a still young nation to its own people, as well as the rest of the world.

I’m told that Dad is best remembered from the early NFB days as a mentor. His clear understanding of and belief in the NFB vision made him the ideal creative leader for the passionate team of young Canadian filmmakers – who often worked 18 to 20 hours a day. The early Film Board employees had a vibrant optimism and sense of commitment to their cause.

.

Grierson assigned Dad to the RCAF as a War Correspondent in 1944 as part of an RCAF film production unit for Britain and Northwest Europe. Dad was in Europe on May 8th, 1945 when victory was declared. During the height of the war, Dad worked with Film Board Director Jane Marsh. The first film they worked on together was “Inside Fighting Canada” in 1942. It featured some spectacular WWII aerial footage. I think Jane couldn’t resist a man in an aviator’s jacket. They had a brief and disastrous marriage in 1948 that lasted only a year. When I once asked him about it, Dad told me that “they were both too nutty” and so they went their separate ways. Jane Marsh was one of Canada’s first female film directors and she left the film board because Grierson refused to give her autonomy as a director.

When Grierson resigned from the NFB in 1945, he nominated Dad as the “natural choice” for his successor as Government Film Commissioner. Then shortly after Grierson’s departure, he was implicated in the Gouzenko Spy Scandal. The Film Board and many of its employees were tainted by their association with Grierson, including Dad. Though Dad continued at the Film Board as the Head of Production, he was shipped to London in 1951 to head the expanding European Distribution Unit.

After his marriage to Jane Marsh ended, Dad became friendly with Margaret Coventry, the Film Board’s Editor-in-Chief. Recovering from her own disastrous wartime marriage, Mom and Dad struck up a connection which lead to a colourful correspondence. She soon followed him overseas and they were married. In 1954 they had their first son, Alexander.

Burmah Shell Corporation

In 1954 Dad left the National Film Board when he got an opportunity to create a documentary film production unit in Bombay, India for the Burmah Shell Corporation. From 1954-48 Dad produced 40 films across the country. His film “Himalayan Tapestry; The Craftsmen of Kashmir” won the 1957 President’s Gold Medal Award for Best Documentary Film.

After WWII and the formation of UNESCO in 1945, there were concerted efforts to use film as a tool for nation-building around the world. India was defined as one of the key emergent countries, rising out of the ashes of colonialism. Dad applied the Griersonian principles he had learned in earnest, helping to shape India’s national film board “The Indian Films Division” following the NFB model.

According to Shama Habibullah, a prominent Indian film producer, “If you show the titles of those films to people today, they’ll say, ‘oh but these are not issue based’. But look at what they did. They were themselves issues. They were the ones that created the concept of how you would delve into finding out what the issues were. Until you knew what that was, which was really like the bricks, you wouldn’t know what your country was to even find an issue in, at that particular point.”

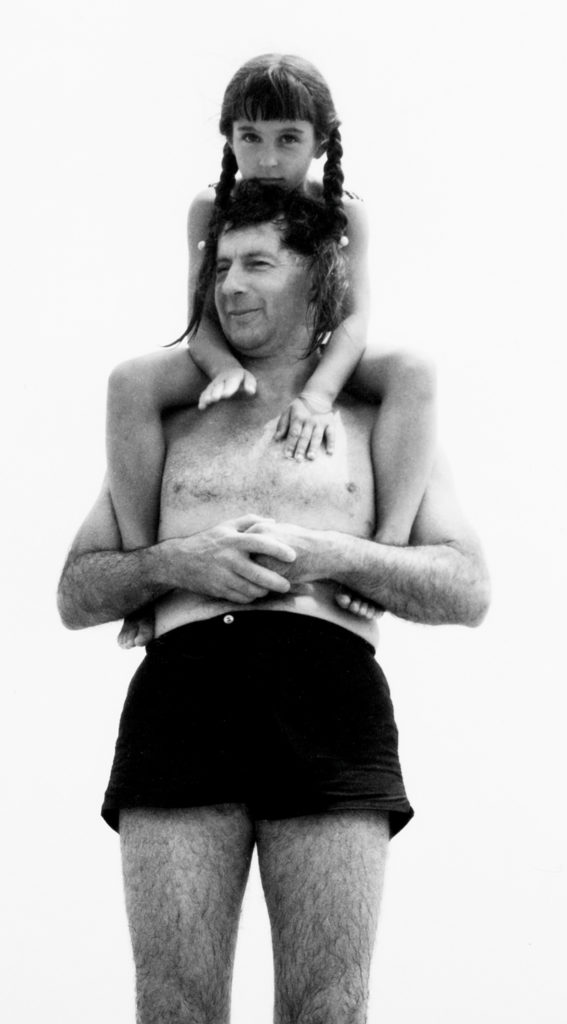

My parents’ experience in India had a profound impact upon them. I was born in Bombay in 1957. When I asked Mom why they baptized my two older brothers but not me, Mom said that they forgot. I think it was really because my parents had become more Hindu than Christian. India laid claim to their souls. I was ten months old when they packed the family on a steamship and we cruised back to London, England after Dad’s contract came to a close.

.

.

The Laurentians

We returned to Canada in 1958. Dad was not hired back to the Film Board as he hoped. After a few months in Montreal, staying with friends, my parents found a cottage in St. Sauveur, deep in the Laurentian woods, followed by a log cabin in Ste. Marguerite Station. I spent most of my time there exploring the woods, fields and lakes, sometimes alone or tagging along after my big brothers. We became independent at a very young age.

Dad freelanced as an editor for other NFB producers. Those films included the award winning film “A is for Architecture” and a two part documentary on Glenn Gould, “Off the Record” and “On The Record”. For two years he became the Host and Moderator of CBC’s Public Affairs Television Series “Let’s Face It”. Dad forged a new kind of relationship with the NFB as an independent producer and produced a film entitled “Four Religions” that he co hosted with universal historian Arnold Toynbee. He then produced a six-part series exploring spirituality and religion around the world with the NFB.

Sometimes my parent’s friends from the National Film Board would come to visit. Norman McLaren and Guy Glover stayed with us on the weekends and once stayed for a whole summer. Norman, who was Godfather to my oldest brother Alex, taught us how to use oil pastels. We would draw pictures together. Alex developed a very unique style of drawing with oil pastels and ink as a result.

.

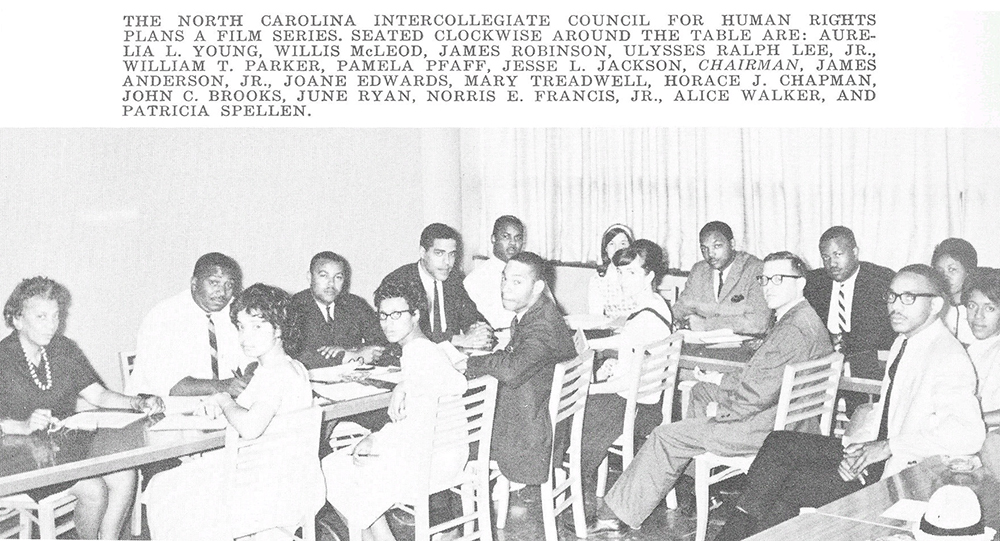

North Carolina State Film Board

In 1962 Dad was hired by the progressive Democrat, Governor Terry Sandford, to set up a Film Board for the State of North Carolina, with the support of John Grierson. We piled our belongings in a VW bus and drove south to a new home in Chapel Hill. The VW van became a family fixture many years. I remember that van as the place where we were all together as a family unit. After staying for one year in the woods of Chapel Hill, we moved to the suburbs of Raleigh. The new Film Board was now built and had a functioning production unit. Mom worked with Dad setting up the editing department and the general operations.

.

Expo ’67

Between 1965 and 1967, Dad was commissioned to create a multi screen presentation for Expo ’67 for the “Man the Producer” Pavilion. Leading up to Expo ’67, Dad’s partner Robert Anderson was commissioned to prepare a report for the Centennial committee to assess Canada’s corporate interest in funding a national film archive for Centennial inspired Canadian content. Both the NFB and the CBC were hoping to garner benefit from this program. As one of many ex-NFB’ers with an axe to grind with his omnipotent ex-employer, Anderson used the report as a vehicle to attack the competency of the National Film Board and it’s current practices, claiming a strong preference for CBC’s productivity. Andersen timed the release of his report to the media just prior to a parliamentary commission on broadcasting, creating a flurry of defensive activity by the Board. Dad was one of the four agents named in the report that had met with prospective corporate sponsors across Canada, gathering information for Anderson, and his status with the Board was once again tarnished.

Around this time, the Film Board was considering candidates for the next Government Film Commissioner. Once again, Dad’s dream of running the NFB was denied. When Under Secretary of State Ernie Steele wrote to John Grierson to get his opinion about Dad, Grierson bashed Dad as a carpet bagger who spent too long away from the “church”. Grierson expressed his displeasure at the demise of the North Carolina Film Board, blaming Dad for his lack of political savvy. And because of Dad’s association with the Centennial Report, Grierson suggested he might cause a political explosion at the Board.

After leaving North Carolina, we found ourselves back in the woods of Quebec. The family moved into a wooded community that ran up a mountainside in the heart of the Gatineau parkland. My Dad formed a partnership with another ex NFB filmmaker who lived down the road from us named Robert Anderson. As soon as we settled in Canada, Dad was commissioned by Tom Slevin, an Executive Producer for National Educational Television, to return to India to direct three films for WNET’s “Creative Persons”: one about celebrated Indian film director Satyajit Ray; one about Ustad Bismillah Khan, a shehnai master, and one about Wealthy Fisher, an aid worker in India.

.

.

After only two years, my parents business partnership with Robert Anderson blew up. They literally lost all their assets overnight in a bad business deal and we suddenly found ourselves back in the old log cabin in Ste. Marguerite Station, living on pork and beans and fish sticks for a few months while my parents regrouped. They hired a teenager named Cathy Morgan who cared for us while they worked hard to pick up whatever film production work they could. Ex-NFB filmmakers Gudrun and Morten Parker kindly shared their Montreal studio and lab space with my parents during this time.

New York University

Then Dad found a job that would prove to be his greatest calling — Professor of Film at New York University’s brand new Faculty of Film. It was 1968. Once again we packed ourselves into the VW Van and drove off to New York. Actually, we moved to Westport, Connecticut, which is a short train ride from Grand Central Station. Dad became a weekend commuter. He had a ‘pad’ in the city where he stayed with a friend.

The kids went off to school and experienced culture shock after attending a small rural french school in Quebec. The schools in Westort were excellent but the culture was preppie and very rich. My big brother Alex had a hard time fitting in. His clothes were different and he couldn’t play football very well. I think Westport really hurt Alex. Nick became a ‘jock’ so he made friends pretty quickly. I was athletic so I could choose my friends too. Alex wasn’t so lucky.

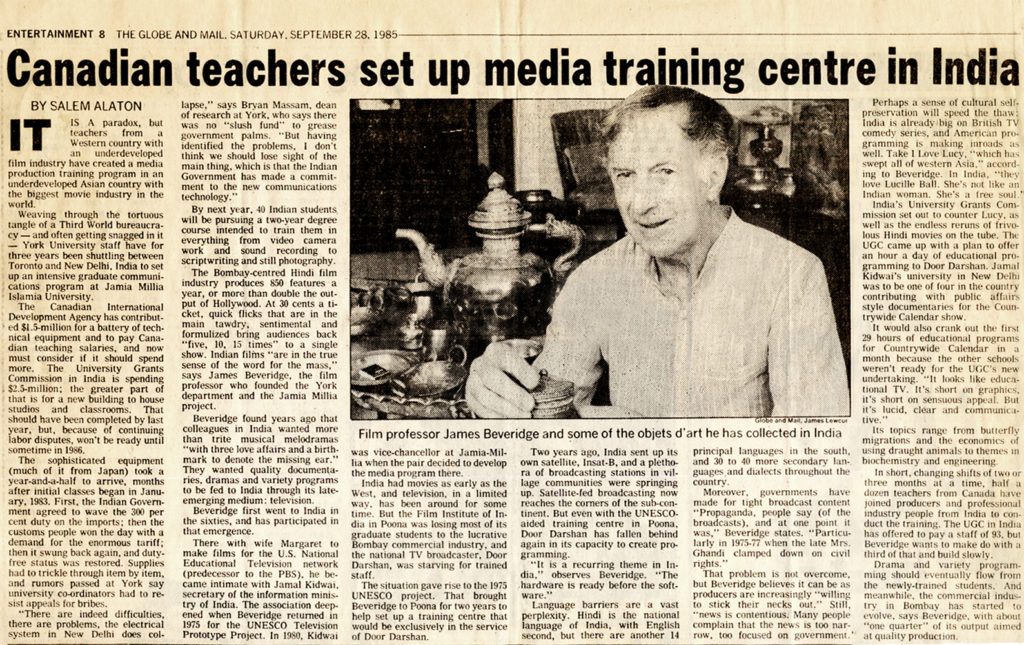

During this time the Vietnam War was raging. Mom encouraged Alex to go to Washington and participate in the war moratoriums. NYU was in the thick of the Sixties Revolution. Dad grew long sideburns. In the summers he went regularly to India and Europe. The staff at NYU called him the “Groovy Professor”. We didn’t see much of him. While making this film I learned that Dad was hired as a Chief Consultant for the Indian Films Division for three years. He also acted as consultant to UNESCO to create a film institute in Poona focused on documentary production, and he taught a 6 week scriptwriting course there.

In 1970, my parents independently produced four very well known Indian music films on Classical Musicians of North India: Amjad Ali Khan, Pandit Jasraj, Bhimsen Joshi, and Vijay Raghav Rao, as well as a film about the Dalai Lama.

.

York University, Toronto

In 1970 Canada’s first university degree program in film was opened. Dad became the Founding Chairman of York University’s Department of Film. Dad was able to draw on his visionary capabilities to design a vibrant program with a strong academic base. He spent two years commuting between Bombay, Poona, Toronto, New York and Westport while he started up the program. By that time my two brothers – Alex and Nick were seeing their classmates getting drafted to fight in the Vietnam war. The family moved up to Toronto in November, 1972.

This was the first time in many years that our family actually all lived together for extended periods of time. I think it was a rude awakening for Dad, living with what had become a resentful though still supportive wife and three surly teenagers.Dad didn’t have to stick around too long though. In 1972, the NFB wanted to make a film about Grierson’s life. Grierson, whose health was ailing, was reluctant to participate, and only consented on the grounds that Dad would be the chief advisor on the project. Dad accepted and became the consultant as well as the interviewer for the film. From the dozens of interviews that he conducted with Canadian and other world famous film makers, Dad then wrote a book on Grierson: “John Grierson: Film Master”.

.

.

In 1975, Dad managed to secure a sabbatical from York and was commissioned by Mobil Oil to make a documentary on the “National Living Treasures” of Japan. He spent 10 months in Japan producing the film “Hands”, which went on to win the Grand Prize at the World Craft Council Film Festival in New York. It was Dad’s most experimental work to date and was technically and artistically superb.At the same time in Toronto, the kids were flirting with disaster. We were in our raucous teenage years with little supervision and a great taste for independance. In the midst of it all, Mom had emergency gall bladder surgery and nearly died from a resulting infection. She was in the hospital for over six weeks. I don’t know if my Dad was ever aware of what was going on with his family at this time, as he was not in regular communication with Mom. When Mom got home from the hospital, she just couldn’t take being on her own anymore with all of the family troubles. She decided to pack up the household, rented the family home and moved to India. Nick and Alex were already in University, so they were deemed fit to take care of themselves. She enrolled me in Woodstock Missionary School – a boarding school in North India, in the foothills of the Himalayas. It was my turn to become forever changed by India.

SITE (Satellite Instructional Television Experiment)

While Dad was finishing his film in Japan, Mom set up her house in New Delhi. Mom was tired of taking a back seat to Dad’s successes, and decided to take matters into her own hands. She began to develop her own strategic contacts. One partnership in particular was made with Jamal Kidwai, the former Secretary of Information and Broadcasting in India. They began discussions about the creation of a very unique school of Mass Communications to be set up in Delhi.

Dad was worried about Mom’s emerging independence and her new ally. After his film project in Japan was over, Dad sought out work that would take him back to India, to be closer to Mom. He found a job based in Poona that was 1400 kms from Delhi, and Mom. He joined UNESCO again, to develop rural educational television programming strategies as part of a nation wide program called S.I.T.E. (Satellite Instructional Television Experiment) to utilize the benefits of an American satellite system that was on loan to India. This project continued from 1975—1978 and made great inroads developing the use of educational television broadcast by satellite as a means of changing and improving the lives of rural Indians.

.

.

I was invited not to return to the Woodstock Missionary School after one semester and so I was shipped off to another school in South India. Between schools, Dad invited me on a field trip with him to a small Maharastran village. It was an experience that Marshall McLuhan would have loved. The UNESCO field tests were in full motion. Dad’s team were installing TV sets in the central squares of selected rural villages throughout the state of Maharastra – to see how the villagers responded to the programming. The villagers were not only affected by the programming, but by the medium of television itself. For the first time in the remembered history of some villages, all castes and both genders gathered in the square to share in the collective experience of television. Their engagement with the television experience was absolute. Their social order underwent an instantaneous transformation at that moment. It was exciting to witness. This was Dad’s idealism in action. Sometimes it really worked.

India Walkabout

After trying a couple of months at the new school, and feeling that I didn’t remotely fit in, I decided to leave. To my parent’s chagrin, I ended up traveling around India on my own or with friends for the next eight months. Not many parents would allow their 17 year old daughter to travel through a foreign country without an adult, but my parents had faith in me and loved India, so they let me go. Either that or they had lost control of me… Low budget travel in India was always intense, often rugged, physically challenging, intriguing and beautiful, and often dangerous for a young single girl.

My parents believed that travel was educational and generally encouraged it. Both my brothers were now exploring the world. Alex headed off to Central and South America where he spent four years traveling on and off, between University courses. Nick explored Europe and Asia in a one year long roundabout and then went back to University of Toronto. In subsequent years I continued to travel between school terms (having returned to Toronto the following year to finish high school) and then University, returning to India, other parts of Asia, and exploring much of Europe. Our family was truly scattered yet we were never conscious of being that far apart.

Jamia Millia MCRC

|

While Dad was finishing the film “Hands” in Japan, writing his book and still teaching at York University, Mom was busy in Delhi developing new work prospects. In 1979 she spearheaded the launch of a six month field study to develop a proposal for Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) to fund the creation of a new Mass Communications faculty at Jamia Millia Islamia University. This lead to a highly successful venture between CIDA, York University of Toronto, the Indian Ministry of Information and Broadcasting and the Jamia Millia Islamia University of New Delhi. The project is credited to her husband James Beveridge and to Anwar Jamal Kidwai (at the time, VC of Jamia Millia Islamia) but my mother was very much at the centre of the project, contributing her passion, insight, organizational skills and knowledge to its creation. It was Mom’s lifelong frustration that in her partnership with my father she was mainly unacknowledged. She was a victim of the changing times. In this case, York University refused to give her a senior title on the Jamia MCRC project despite her critical participation.

Mom, Dad and Jamal Kidwai were the driving forces behind establishing the Jamia Millia Mass Communications Research Centre in New Delhi, India. This project was both my parents crowning achievement and represented a culmination of my father’s many skill sets. Mom and Jamal Kidwai had become quite close, and they worked together with Dad for many years, each providing a unique and vital role to the fulfillment of their creative vision.

The Jamia became a hotbed for social activist journalism. Mom, Dad and Jamal Kidwai was able to design a curriculum that focused on developing not only the technical and creative skills of their students, but also their social consciences. He drew heavily on his Griersonian principles, encouraging filmmaking for a social purpose. India’s young filmmakers responded to their call.

.

.

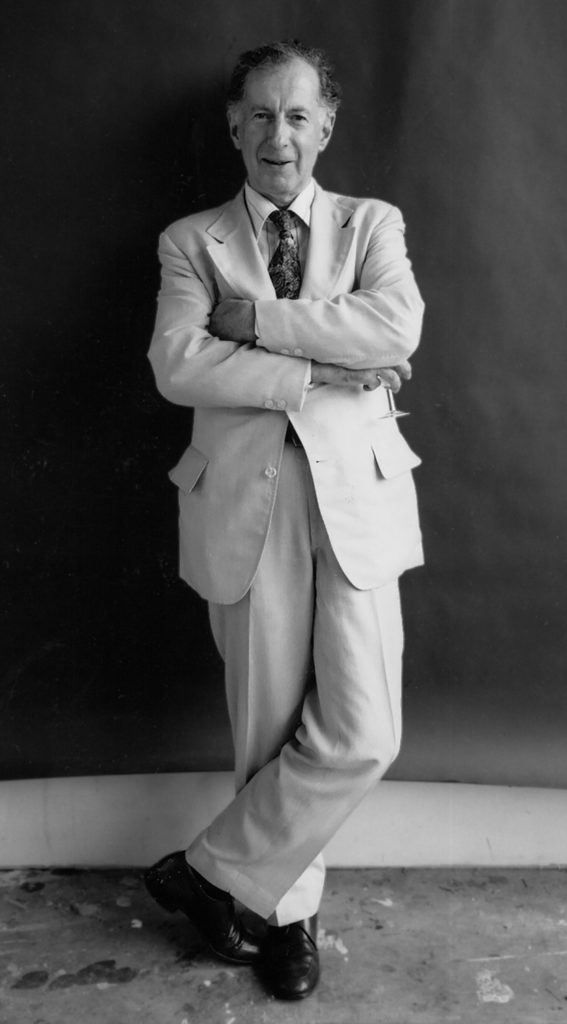

The Final Years

In 1987 the Jamia Millia MCRC was officially transferred from CIDA’s control to the Indian government, and my parent’s involvement tapered off. My Dad had started to get absent minded and was not able to concentrate very well. In 1988, in Toronto, he was diagnosed with Multiple Infarct Dementia, an ongoing series of mini-strokes to the brain, which has a degenerative effect. One year later, my Mom was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She passed away in Toronto in November, 1990.

Dad was given a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Academy of Canadian Film and Television in April of 1991. At that same moment, I was scattering my Mom’s ashes in Rishikesh, India. When I returned from my trip, my father was diminishing rapidly.

My relationship to Dad changed dramatically in those last few years. I became his trusted caregiver. I made sacrifices for him. It became a relationship of mutual love, respect and humility. It was only then that I realized how little of his life he had shared with his children. But by then it was too late to learn about him, as his ability to express his thoughts was severely compromised. His speech had become very refracted and he was delusional. It was cruel for a man of his acumen. Dad mercifully passed away from complications arising from his disease in February, 1993. He was 75 years old.